THE BEGINNINGS OF PHILIPPE TOURNAIRE

Self-taught, I groped my way around for a long time, using the knowledge I'd picked up from my family and on my travels. In Morocco, for example, I met craftsmen who worked with very rudimentary tools.

A cellar to learn the ropes

By the time I started my apprenticeship as a radio electrician, I'd already been making jewelry, clothes, weaving and even shoes for a long time. My rather modest parents had taught me that if you wanted something, you had to make it yourself. System D was passed on to me and my brothers at an early age. If I liked something, I didn't think about going out and buying it, but I did think about how I could make it. The Musée de l'Homme in Paris gave me something to think about, to answer the recurring question "Why?Located at the Trocadero, this museum showcases the diversity of humanity in anthropological, historical and cultural terms. What attracts me here are the everyday objects of all the civilizations that have more or less disappeared. My fascination with this heritage led me to research and reproduce how early man shaped his objects, and why they have gone from being utilitarian to works of art.

I really liked jewelry. As a radio electrician in the countryside,

you have to be very versatile, so I used to install machines and work with copper. I was lucky enough to have learned to tinker from grandparents who were carpenters and cabinetmakers on the one hand, and farmers on the other, which also helped me a lot. These very varied trades, which require ingenuity and know-how, have enabled me to achieve anything I set my mind to. For example, my grandfather, a carpenter, had a forge where he made his tools. The apparent ease and know-how of my grandfather, with whom I spent hours in the workshop, opened the door to craftsmanship and gave me the keys to understanding the long process.

I was also lucky enough to realize very quickly that by concentrating on small objects, my asthma bothered me less, and I forgot that I had to breathe. Asthma is both psychological and pathological. Art therapy didn't exist, but I'd found something that soothed me and did me good, in addition to sport. Listening to my body, concentrating and making art objects were the key, the trigger...

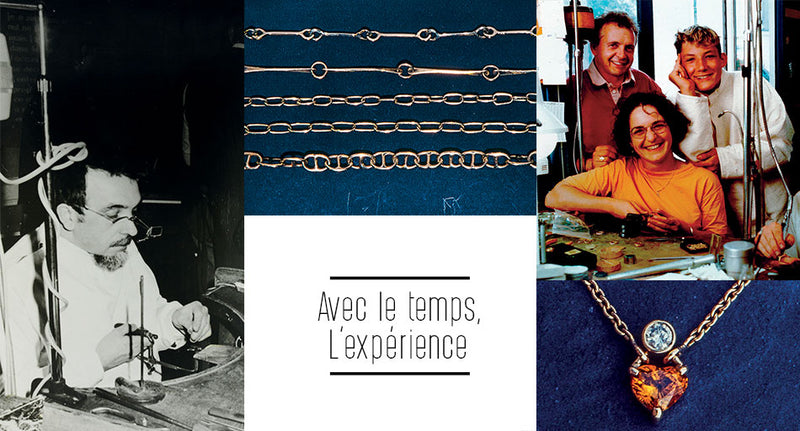

After 20 years of living as a family in what was at once a home, workshop and store, we moved in 1971 to Baffie, a hamlet 1 kilometer from Saint-Germain-Laval. My parents had restored a very old, semi-buried house. The cellar overlooked, and still overlooks, a path that leads to the famous Baffie bridge and its chapel. At the age of 22, I seized the opportunity to set up a workshop there. As I couldn't stand upright, I dug out 20 centimetres of the floor and raised the door. Once the walls and floor were clean, I set up my workbench, rudimentary tools and an interior display case to showcase my first creations. I also set up a makeshift bedroom in a corner, as I often worked late into the night... I lived there for 7 years, in a kind of autarky, working slowly and long on my creations. Completely untrained in any technique, I tried out everything I could think of, using any metal or object that might inspire me. Little did I know, then, that this work was an essential gestation period for the birth of my style, and that two reasons prompted me to start working only in the mornings when electricity was on. My passion for jewelry, which I was always making for friends, and the arrival of the first integrated circuits. From one day to the next, we had to work on machines we didn't know how to operate. At the beginning, when we had to repair a lamp or a transistor, there was an intuitive side to it, you had to understand how it worked, it was like a treasure hunt for me. When integrated circuits came along, we just became parts changers. We had to measure the voltage and if it didn't match the specifications, we had to change the integrated circuit, but we had no idea why. Working like that didn't interest me at all, there was no longer the challenge aspect, finding a fault was a bit of a game. I knew then that the profession would continue to evolve in this direction, and that it would lose all its interest in my eyes. Besides, I needed to find time to respond to my ever-growing creative urge.

"I never thought jewelry could become a profession".

For a whole year, I "pestered" the taxman in Roanne to authorize me to make jewelry under a special status. There was no such thing as "auto-entreprenariat" or "micro-entreprise"; you became an entrepreneur straight away. VAT on luxury goods was 33%, and if I'd gone ahead without a status, it wouldn't have been possible. So I studied the legislation with a friend, and one day the solution came to me: I would call myself a "precious metal sculptor".precious metal sculptor". I went back to see the guy at the tax office in Roanne, Monsieur Lopez. The names of those who help you move forward remain with you. Then, in March 1973, during a last meeting, he said to me:"Well, your story isn't going to be played out over millions, so I'll give you this status". Demand was growing beyond the friendly sphere, and I had to practice legally. So I obtained my 1st Master stamp and authorization to buy and resell precious metals with a police book. It took me two years, visiting Mr. Lopez regularly, to find the solution. As an artist, I wasn't subject to VAT, so I had fewer constraints and less paperwork than an entrepreneur. When I officially started, I knew nothing about the world of Jewellery and gemstones. I was helped by people who gave me the basics to do a good job. As early as 1973, I regularly rubbed shoulders with a stone cutter from Lyon by the name of Jacques Secretan. I used to go to him for answers to all the questions I had about stone. Even if they were sometimes bizarre, he always tried to answer them. He was a very important person in my apprenticeship at Jewellery , helping me to understand gemmology and forge my own vision of stones.

A diamond dealer on rue Mercière, Jean Grosfilley, also took the time to teach me about this exceptional stone. Above all, there was another person who was very influential in my early years. A jeweller, Meilleur Ouvrier de France, by the name of Jean Giraud, whom I met at the Saint-Étienne Fair when he was working in public. He had a store in Saint-Chamond and was the first person in the trade to encourage me. He invited me to visit him in his workshop, which was a great vote of confidence. It took me 3 years before I dared to go...

All these people, encounters, persistence and hours spent at the workbench have taught me how to work. It gave me the opportunity to build an identity, a style that is reflected in my creations.

In the beginning, I was in the country, I had no expenses, I wasn't married and I didn't have any children yet. I pursued "my bohemia", then word-of-mouth brought me more and more customers who kept me working and living. I continued working part-time as a radio electrician with my father until 1976, after which I devoted myself entirely to jewelry. I also set about building a small house above Baffie with my own hands. I lived there from 1978, the year Romain, my first son, was born.

I have very fond memories of my cellar, where I learned a lot, and not just about my job. Radio fed my mind and my curiosity. While I was working, I listened to Jacques Chancel on his " Radio-scopie " program, where he always invited fascinating people who encouraged me to read their books. But I also listened to France-Culture, where science and history were very present. In the end, I learned more by listening than by reading or going to school. I had no training whatsoever, and it was my great good fortune not to know how jewelry was made. I just did what I felt like doing.

It's a constraint at first, because if you don't know how to do it, it takes longer to make. But I was able to reinvent existing techniques in my own way and create my own know-how. And since I had a very good knowledge of carpentry, forging and electronics, these skills connected and I found alternative solutions. From this inconvenience turned constraint, my style and talent were born.

In 1979, the price of gold rose from 4,000 to 15,000 euros per kilo in the space of a month or two, when the USSR entered Afghanistan. From one day to the next, the threefold increase in my raw material costs put a huge brake on my business. At the same time, to earn a little money to finance my materials, I had a friend who dreamed of opening a nightclub. He had helped me fit out the cellar, so I gave him a hand.

In 1981, the year Mathieu was born, the project came to fruition and the " Vers de Gris " opened its doors. It was in the evening, so I could earn a bit of money bartending and DJing. I met people who had dynamic businesses in the area. Their success gave me confidence, and the idea was born that I too could set up in the city.

The guarantee of uncompromising craftsmanship

OUR TITLES AND LABELS